A Very Strange Life

Personal Experiences: From Skeptic to Explorer

THE FREE BOOKS BY Chip Cook

WELCOME

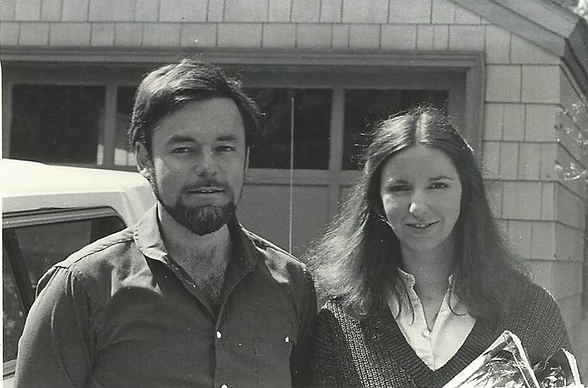

Chip Cook and Ann, 1984

AN AUTHOR'S NOTE TO THE READER

I present to you three very different types of real life stories. Each serves an important role. Unbelievably they are all connected to my life.

Book 1- Surviving Detroit may seem like an American Graffiti type of autobiography.

My purpose is to set the stage for what is to come in books 2 and 3. Also to provide the reader a measure of who the Author is. In hindsight, the only two possible things that could be unusual were my grandmother's advice and what I called my strange luck.

Book2 - A Very Strange Life is the second part of my life. It takes the reader on a journey of strange events that lasted, to various degrees, a lifetime. By strange, I mean paranormal influence and intent. They form my collections of puzzle pieces.

Book3 - Making More Waves is my attempt at a rational explanation (a model) for irrational observations. I use my unexplained puzzle pieces in science and my paranormal observations to make a model of possible causation. My model only serves as a starting point.

I hope you will enjoy my unusual journey

Chip Cook

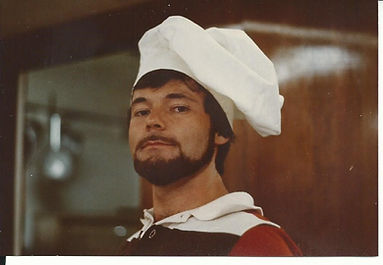

BIO

.jpg)

.jpg)

An Outline of My Personal History

No one is born a heretic—but some parents might disagree with that statement. Children live in worlds of their own making, and maybe that’s helpful from an evolutionary standpoint. But for parents trying to maintain control, it can be a real challenge. I was one of those children—a true heretic in the making. If you want to understand my perspective, it may help to think of me in those terms.

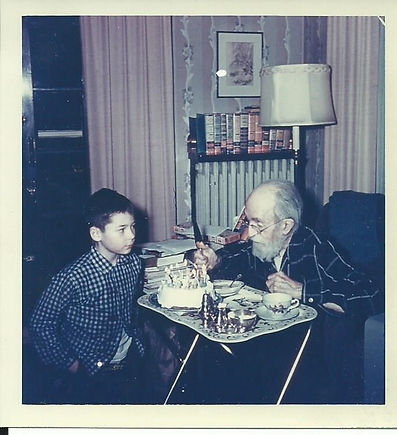

I was born on February 22, 1949, in the city of Detroit. I had a loving family, and each member saw the world in their own unique way. We lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood. I had been raised to be socially colorblind and never understood racial prejudice. So it was easy for me to form friendships with the kids on our street. We played in the alleys and streets of a city teetering on the edge of racial collapse.

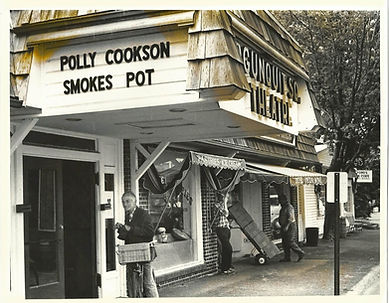

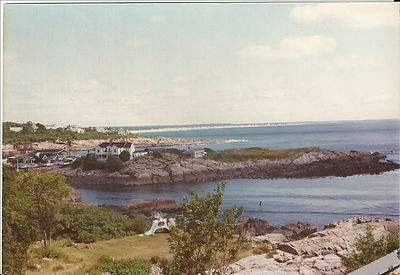

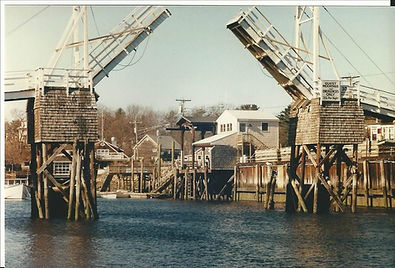

Every summer, my family would vacation in Maine—eight hundred miles due east of Detroit, and an entirely different world. We had been going there since 1914. It was an old art colony and ocean resort with a mostly white population. As a child, I accepted the contrast without thinking much about it. At first, I was just as comfortable on the cliffs and beaches of Maine as I was in the Detroit alleys with my friends. But as I grew older, something shifted. I no longer felt like I fully belonged in either place. That outsider status shaped my perspective. It made me suspicious of almost everything—and everyone.

Religion was another stumbling block on my road to skepticism. Despite being raised in a very liberal Protestant household, I still wanted more proof than “because it was written.” It didn’t sit well with me that my belief system had been determined by where I was born and what faith my family followed. I was the kind of person who needed to see things for myself.

Eventually, I found a home in Agnosticism. That philosophy allowed for the idea that answers exist, even if we don’t yet understand them. I preferred not to stand in judgment of anyone else’s beliefs, and I didn’t feel the need to fully commit to one myself. If there’s nothing after death, there’s nothing to worry about. And if there is something—well, we’ll deal with that when we get there. That was the logic I lived by.

But then something happened. A series of strange experiences turned everything upside down. They became what I now call my rabbit-holes. I didn’t find God—but I did find something unusual. And that discovery became the subject of this book. I became a heretic not just in philosophy, but in science as well.

Another challenge I faced was a learning disability. I was word-blind. If I looked at a word and tried to picture it with my eyes closed, I couldn’t. Imagine learning to read and spell under those conditions. Eventually, I was labeled dyslexic—a broad term, but accurate. Yet challenges like that can be turned into strengths. They define us, especially in how we respond to them.

I went from the bottom of my class to the very top. The drive to overcome that disability gave me tenacity and willpower. I also had the confidence of youth, the belief that I could do anything I set my mind to. Maturity has made me more realistic, but I still have faith in my reasoning ability—and I’m still determined.

While I couldn’t visualize words, I found abstract reasoning to be intuitive. Mathematics made sense to me. In math, things are either true or false. You can prove a concept using the structure and language of the field. To me, mathematics was about connecting the dots—understanding relationships between abstract ideas. Science is built on this same principle. Through mathematical models, we can predict phenomena, measure the universe, and create entirely new technologies—from smartphones to life-saving medicines.

Science is what separates us from living purely reactive lives. It’s what drives progress. Challenges make us stronger, both as individuals and as societies. And yet, I now find myself in the very odd position of being a scientific heretic. As great as science is, I believe it has missed something important. Something big.

When I was five, I learned the value of a dollar. Every week, I earned one for doing chores—mostly taking out the trash. I was responsible for buying anything I wanted. If I couldn’t afford something, I had to figure out how to earn more. That taught me resourcefulness early on.

My teenage years were split between two places: Michigan and Maine. In the fall and winter, I studied almost nine hours a day or worked weekends around Detroit. In the spring and summer, I played, swam, and worked at the resort town in Maine.

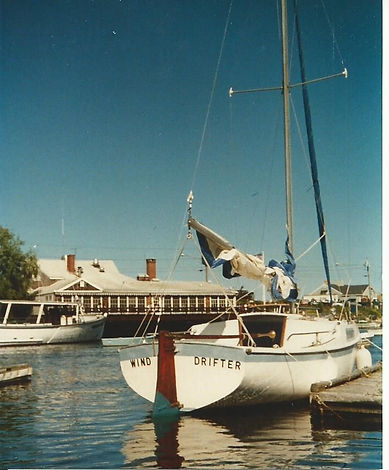

At fourteen, I bought my first sailboat. I’d never sailed before. I’d only read about it. But I taught myself to sail and took ownership of that boat in a single day. It felt natural. That boat was the reward for years of saving and dreaming. My family deserves credit—they let me follow my heart and face “safe dangers.” More character was built during a single stormy sail than I could have gained anywhere else. I called it “kissing the cobra”—a dance with risk where timing meant everything.

Luck, however, has always puzzled me. I’ve always been lucky—too lucky for it to feel random. I’ve told myself that luck is just anticipation plus navigation. But the pattern has persisted. As my grandmother once said, “You must have been born to be hung.” Not the most comforting saying, but she meant it kindly. It’s not the worst problem to have, but it raises some philosophical questions.

People have described me in many ways—introvert, class clown—but one trait has followed me throughout life: I don’t always play well with others. Maybe that’s the result of being an outsider. I always assumed I would marry and have children, but that didn’t happen. I had close relationships, many of them romantic, but when those ended, the friendships often ended too. It was like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

As time went on, I stopped worrying about it. So many of my peers were divorcing, it didn’t seem like I was missing much. In my sixties, I found myself surrounded by younger friends who didn’t understand how I had lived. I skipped marriage, but found other ways to build extended family. I felt like I needed to explain myself, so I wrote Rabbit-Holes of Wonderland and later Forty Dances. Not all strange events are paranormal. Some relationships are strange enough on their own.

I wasn’t a playboy or a serial dater, but some of my extended family would beg to differ.

My goal in life has been to be carefree—but not lazy. I’ve worked hard to earn that freedom. Owning my own time was essential. Financial stability was, too. And I’ve learned that we are shaped most by how we respond to challenges. Without them, we’re just waiting to die.

Helping others has given me purpose. But I’ve struggled to distinguish between helping and enabling. I’ve made mistakes. Still, life has been generous. The more I give, the more I seem to receive.

In spite of a few regrets, I’ve enjoyed the journey. The strange, disorienting events I’ve experienced have changed me. Some of it has been hard. These odd moments don’t go away. I thought writing them down would be enough—but every answer led to more questions.

Trying to be accurate created new challenges—especially when it came to privacy. And even worse, I couldn’t prove what I had seen. Not scientifically. So I would put the book away and try to forget about it. But it became like a six-hundred-pound gorilla at the dinner table. I couldn’t ignore it forever.

I believe something vital is being missed in our collective understanding of existence.

And that’s why I wrote this book.

COMMUNITY VOICES

Share your experiences and join the conversation on the forum. Let's explore together!

Chip Cook, FORUM MODERATOR

Join our community and share your thoughts. Your voice matters!

Hakan Akdogan, FORUM MEMBER

The forum has been a great place for me to connect with others and learn from their experiences.

Karen Blackwell, FORUM ENTHUSIAST